CITY ARTS, SEPT 2013

The Last Look

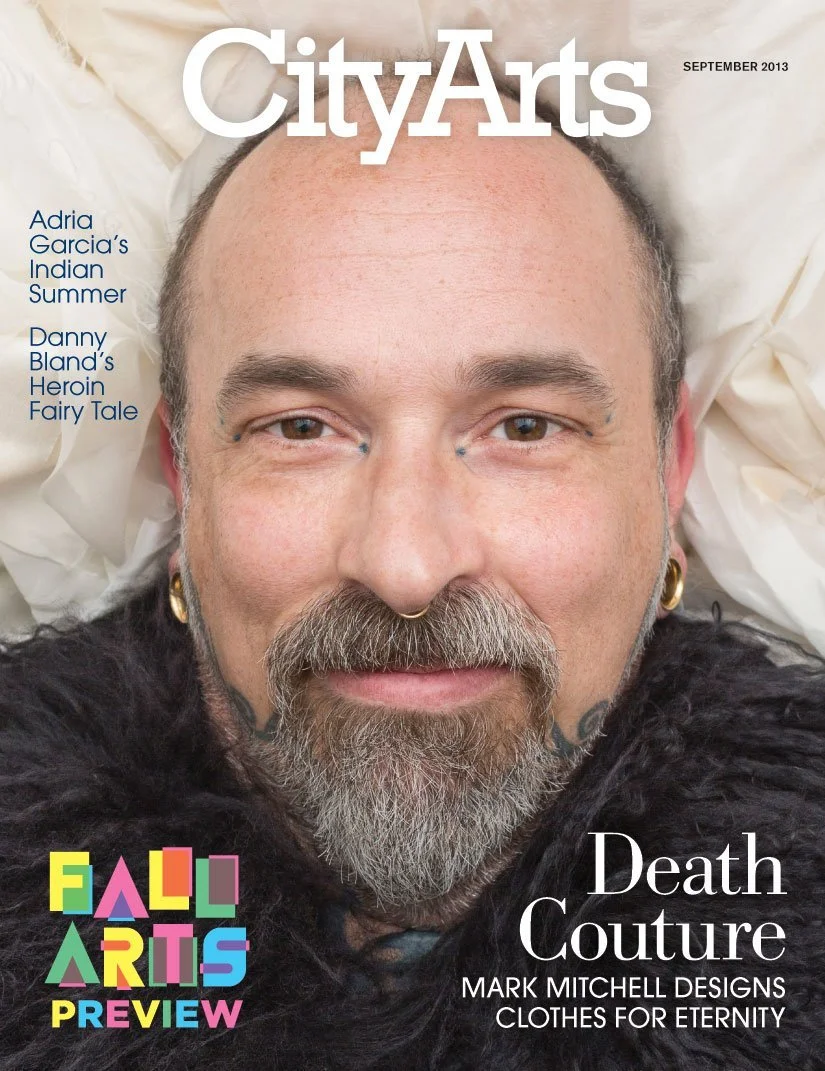

Mark Mitchell’s unconventional take on loss, life and dressing for eternity.

by Amanda Manitach

City Arts Magazine, September 2013

Cover photo by Steven Mitchell

One of Mark Mitchell’s models stands statuesque in a recently finished gown, her body sheathed head-to-toe in cascades of gauzy, milk-white silk. Stiff ruffles that look like they could be made from the plucked petals of white camellias wrap around her shoulders and swaddle her throat like froth. Her eyes are shut serenely as she is photographed.

Is it possible to envy the dead their clothes? Because this couture gown isn’t made for the living.

Photos by Steven Miller

Mitchell has been designing clothes full-time for only five years. After keeping a relatively low profile, he’s having his first museum show this month at the Frye Art Museum, on view Sept. 21 through Oct. 20, which starts with a very unusual fashion show on Sept. 20. Suffice to say, the models won’t be prancing up and down a traditional runway.

Though hardly anyone has seen a finished garment, the collection he’s showing, Burial, is causing a stir. “What I’m doing doesn’t really exist in the world,” he says. “If you Google it, there’s just me.”

Mitchell himself is an arresting man, his appearance as fascinating as his work. He’s covered with tattoos—even his face, where ink peeks out from his salt and pepper beard. The day of my visit to his Capitol Hill studio, he’s wearing a black T-shirt depicting extra-hirsute versions of the members of KISS. It’s KISS and Planet of the Apes melded together, he explains, a favorite piece he purchased at a vintage shop years ago. The rest of his ensemble includes camo pants, a red kerchief tied around his neck and worn leather moccasins decorated with little beaded skulls in headdresses.

“Bury me in this,” Mitchell says, “I’d just want something easy for my partner.”

The sentiment is ironic considering his recent work, but it suits his vibe. This is a man who isn’t motivated by excessive fashion for its own sake, but by love that extends beyond death, love that’s found expression through a revolutionary mode of dress.

***

Mitchell’s ongoing relationship with death isn’t a fling. He grew up in a conservative, small town in central Illinois—“a red, red town.” His father was a union man who dabbled in local politics and became mayor for a year when Mitchell was in grade school. Mitchell was more creative than political; he preferred sneaking around, trying to teach himself to sew, knit, crochet—something not smiled upon as a pastime for little boys.

Though he was designing clothes for friends as early as junior high, it wasn’t until college that he really began learning the tools of the trade. He studied costume design at Arizona State University for a few semesters, then got a summer job making costumes at Phoenix Little Theatre. The gig turned into a full-time job and Mitchell found himself in a community he loved, doing what he loved, developing the career he always wanted. But it was the beginning of a bleak phase that would profoundly contour the rest of his life.

For nearly two decades, the AIDS epidemic devastated Mitchell’s community. Mitchell himself contracted HIV during that time.

“In the late ’80s, AIDS was just walking around with you every day,” he says. “I was sick at that time and not necessarily expecting to live. Those days became all about exploring life, about living in the day to day, which after a while becomes dangerous.”

Mitchell left Tempe for Los Angeles in ’84 and soon followed friends to Seattle, which was in the midst of a theatre renaissance, with no shortage of costume design jobs. Relocation provided no escape, however. Seattle too had been hit hard by the AIDS epidemic and Capitol Hill resembled a horror film, according to Mitchell, with “living skeletons walking around everywhere.”

The deaths of friends and lovers took their toll. Heartbroken, Mitchell ejected from the performance community. He quit designing and got rid of or gave away all his work. He took up professional tattooing and plunged into drugs and alcohol. Though ensuing years of unchecked substance use barely served to band-aid his grief, one bright spot emerged: In 2002 he met his future husband, Kurt Reighley, a writer and radio DJ who was spinning at clubs around Seattle at the time. Their budding relationship was a turning point.

Waxie Moon

Photo by Tim Summers

“I realized I wasn’t going to die and that it wasn’t cute to be drinking as much as I was,” Mitchell says. “Maybe the medication was going to work for me. As I turned my life around, I realized making clothes had always been my dream.”

He took up needle and thread again. He designed some notable burlesque costumes, like the red tulle gown worn by Waxie Moon for his 15-minute-long drag striptease to Bolero last year at On the Boards. In 2010, he collaborated with Anna Telcs on the jaw-dropping Dorothy K Bow Dress, a lace gown with panniers covered in hundreds of black silk bows, for an Implied Violence exhibition at the Frye. And he almost made it onto Project Runway.

“I praise whomever above that I wasn’t chosen that day,” he says. “It directed me away from where I was going, from burlesque.” Instead, it directed him toward Burial.

***

The concept for Burial began with an urn. A little over a year ago, artist and entrepreneur Greg Lundgren curated an exhibit called The Softer Side of Death, a showcase of unconventional cremation urns made from fabric, at Lundgren Monuments, the First Hill storefront for Lundgen’s unconventional headstone business. Mitchell made a drawstring urn using 275 pieces of diaphanous hand-dyed ombre silk—and stole the show. Even when resting, static, the piece seemed ready to levitate, like an otherworldly, effervescent jellyfish. (It was designed to be released in the sea where the fabric will disintegrate and the ashes disperse.) The urn whetted Mitchell’s appetite; what might an entire collection of beautiful shrouds look like?

Lundgren felt Mitchell’s urn, in particular, demanded contemplation. “Why would you spend so much time making this? Why would you pay thousands of dollars to own it, only to toss it into the sea?” he asks. “It is impractical and almost absurd. And it is the embodiment of what love is. All of Mark’s work is impractical, excessive, temporal, and the only thing that holds it together, that justifies it, is love.”

Shortly after The Softer Side of Death, Mitchell got to work on Burial, fitting and constructing garments in his small Capitol Hill studio. The space, built in a loft in his home, reflects the intimacy of his practice. The walls are layered with pinned-up ink drawings, pattern blocks and fabric samples peppered with pictures of Mitchell’s muses, like an iconic black and white photo of controversial artist David Wojnarowicz and a poster of singer Klaus Nomi with his Pierrot-like maquillage and pointy hair. Pale chiffons, crepes and gauze are everywhere, piled, filed, folded. Skeins of silk bouclé yarn and delicate knits-in-progress litter the tables, shimmering.

There’s a conspicuous absence of modern machinery in the workspace. Instead, an old metal sewing machine sits tucked in a corner. It’s a Pfaff 130 from 1954 that Mitchell bought years ago for $125 on Craigslist.

“It’s our favorite machine,” he says. “We fight over it all the time!”

Mitchell shares his studio with a small crew of four assistants and interns. In recent months, they’ve produced dozens of pieces, including accessories and undergarments, almost all of which are made using hand-sewing techniques that date back to the ’30s and ’40s. As we speak, Mitchell runs his fingers lightly over a pair of lustrous, over-the-knee stockings made with loosely knit silk thread. From another nook he retrieves a bundle of top-stitched chiffon gloves with exaggerated, long cuffs to cover stiff fingers. He’s even made footwear: goat leather moccasins for some, silk slippers with embroidery across the soles for others. Everything is shades of white, inside and out.

Some details of the collection may never be seen. Mitchell opens a gown to reveal a flight of doves embroidered across the lining. Inside a secret interior pocket of a silk ruffled jacket the words “my darling boy” are stitched in ivory thread.

Burial gown

Photo by Kelly O

A few fundamentals are consistent throughout the collection. One is the use of silk, the primary material for all the looks and a traditional element in ceremonial and ritual clothing. He’s also very conscious of how his materials are sourced: Everything is 100 percent natural and renewable, down to the smallest detail. For example, the 84 handmade wooden buttons running up the front of one gown, from neck to hem, are each painstakingly covered in silk and fastened with handmade loop closures.

Mitchell recently taught himself to make buttons; it took him three days to perfect the process and make a single button the way he envisioned it. On a garment that will dress someone for eternity, three days dedicated to a button doesn’t seem so absurd.

As Mitchell shows off the details of his works in progress, he refuses to reveal too much about the museum performance itself. It will be peaceful, he promises. And the people modeling the garments will be as important as the clothes.

He’s been working closely with his models—whom he also refers to as muses—for the past year. They include clothing designers Davora Lindner (photographed during my visit) and Maikoiyo Alley-Barnes, burlesque star Marc Kenison (aka Waxie Moon), and close friends Ro Yoon, Alexandra Cartwright,Dominic DeNardi and Rhonda Faison. Some he’s known for ages; others he came across on Facebook and invited to be part of Burial based on their unconventional personas and looks, like mother-and-son pair Kook Teflon and Sailor Hank.

Jo-Anne Birnie Danzker, director of the Frye, says Mitchell’s work is at home in the Frye because it harkens to a revolutionary designer-patron relationship envisioned by Secessionist artists like Henry van der Velde, Margarethe von Brauchitsch, Richard Riemerschmid and Bernhard Pankok, artists whose work anchors the Frye’s permanent collection. Responding to drab and dry turn-of-the-century dress reform movements, Secessionist artists collaborated closely with women not only to free them from arbitrary trends of the fashion industry but to make ensembles that reflected individual personality.

“Burial lies within this artistic tradition,” Danzker says. “Mark is liberating the dead body from arbitrary choices, and from austerity.”

***

Photo by Steven Miller

“Burial does have a lot to do with the deaths I’ve experienced,” Mitchell says.

Dressing for death has always been one way of dealing with death. During the Victorian period, mourning attire reached a fever pitch of formality, extending “to funereal trimmings on bird cages and ladies’ underwear,” as Lou Taylor notes in Mourning Dress: A Costume and Social History.

The excessive costume culture that surrounds death and mourning has almost always existed for the living. The dead were less lucky in this department.

“They’d slap a little shroud on a person with a nice bib front with some pleating and a bow, but the rest would be unfinished,” Mitchell says. “Totally just cut off across the bottom—just the little bit that shows is decorated and the rest is just a cheese cloth wrap around. When I saw this at the Museum of Funeral History in Houston, it made me so sad. I was like, Oh God, please bury me in a complete set of clothes! You’ll find that my ensembles are very complete.”

The nine ensembles in Burial are described as “suggestions” in the show’s press release. Suggestions for what exactly? Mitchell, who is constantly dipping into an encyclopedic knowledge of history, says the language borrows from vintage advertising jargon.

“I like the wry 1930s fashion magazine aspect of the term,” he says. “Like, Suggestions for Beachwear, 1936! I’m not making demands or expecting anyone to want to do this. I’m suggesting that these are beautiful. Why not this for eternity? You are going to die, and if you want something amazing to wear, these are my suggestions.”

For Mitchell, levity and serenity are slowly but surely replacing grief.

“I mourned so many people for so many years,” he says. “It took me reaching the age of 50 to get to the point I couldn’t carry them around anymore. Part of my being here is I have to do something amazing with my life to make up for the fact that they’re not here.”