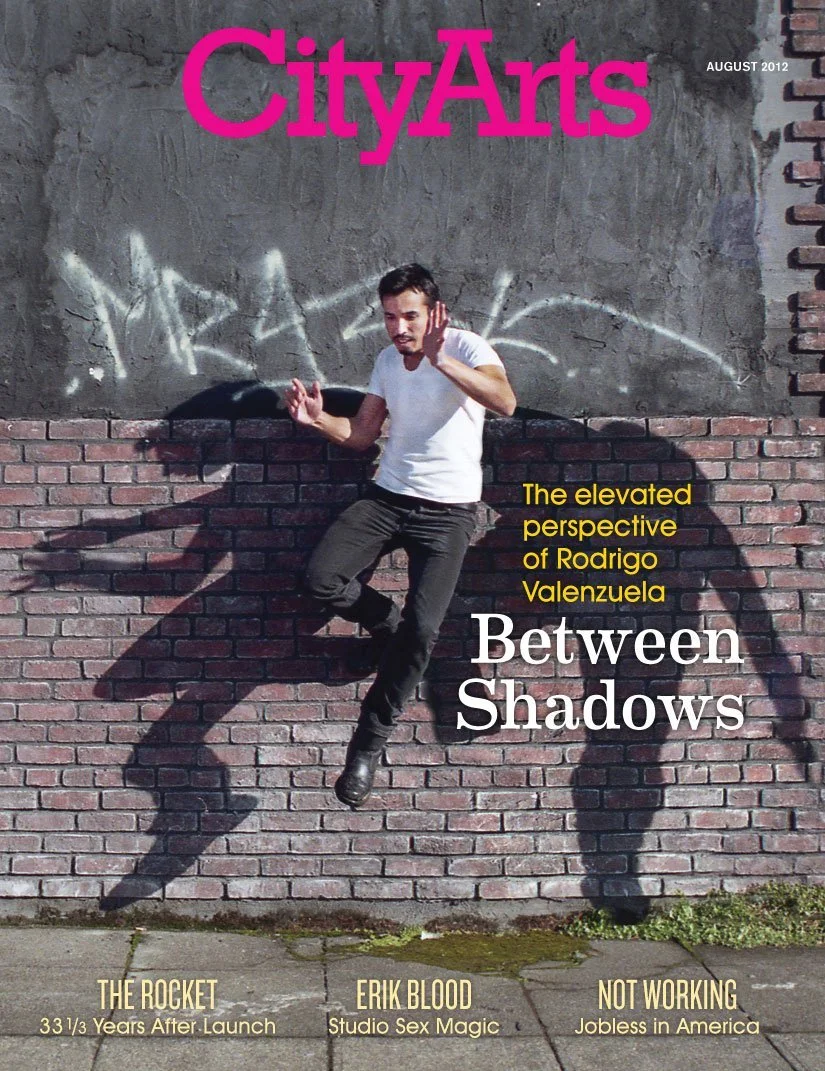

CITY ARTS, AUG 2012

A Flash, Then Nothing

Traveler, filmmaker and photographer Rodrigo Valenzuela finds truth between fiction and reality.

by Amanda Manitach

City Arts Magazine, August 2012

Cover photo by Rodrigo Valenzuela

Rodrigo Valenzuela is driving through the southern California desert toward Joshua Tree. His pickup hums quietly over interminable roads, kicking up a fine dust. The pavement throbs with bright, lazy, hundred-degree heat. He keeps the windows rolled up, the radio off. His eyes are locked on the horizon. Valenzuela is here—the middle of nowhere—to shoot footage of places that don’t exist.

This desert trek is an exercise in quietude and loneliness, feelings Valenzuela is accustomed to, even savors. He travels light—a few clothes, a cell phone with bad reception, some cameras and tripods. As he drives through the rolling, empty scenery he scans the landscape, searching for something specific but undefined: an isolated building, a stranger, a striking geological formation that will trigger a fantasy in his imagination.

When he gets back to Seattle, Valenzuela will alter the material he gathers on this drive, transforming this sun-baked desert panorama into an illusory landscape, sceneries digitally stitched together from multiple photos or videos. A previous expedition produced tonally-rich, five-foot-wide black and white photographs of arid plateaus strewn with toothy rocks, derelict shanties under mercury-bright skies, nonsensical rubble and strange pyramidal cinderblock formations. The photographs were edited so meticulously that you can’t tell anything has been changed—or that these surreal places aren’t real at all.

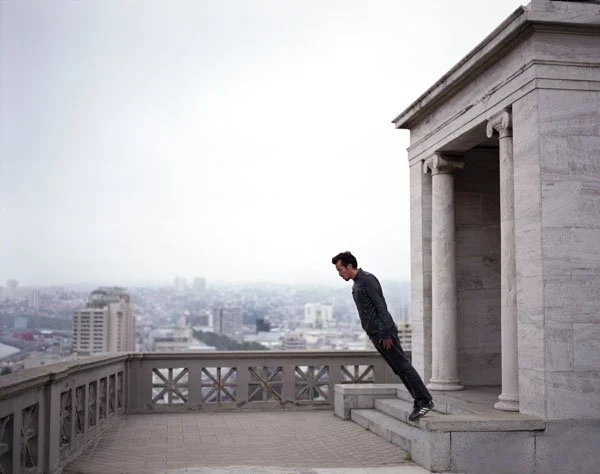

Fixing the Architecture #1

On this trip, Valenzuela will film a long, aimless evening stroll. He pulls the truck off the road and parks in the gravel swale. He gets out and starts walking, camera pointed towards the horizon. He will keep walking from sunset to sunrise.

“I want to transmit that feeling of being lost and lonely, but with a sense of direction, a destiny,” he says later. “That’s something inherently good about walking: Wherever you go, it’s gonna feel like you arrived somewhere. It’s like art-making. Even if the destination is undefined, the process is satisfying.”

***

Valenzuela has been moving all his life: Chile, Montreal, Boston, Olympia, Seattle. Over the past two years, he’s produced a body of work that’s politically and aesthetically charged.

“As an immigrant, I understand a certain pressure to become like Americans,” he says. “But I never felt tied to a nationality, to a place or to the past.”

His films and photos tell stories about transitional spaces and discrete gestures, deftly superimposing the formal beauty of neoclassical painting against a narrative backdrop of political institutions and individual isolation. His work communicates a gut-wrenching listlessness, lack and liminality inscribed on migrants transitioning between nationalities and political identities.

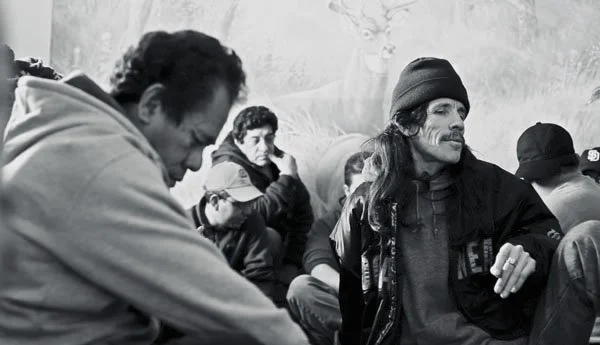

2012 video still from Diamond Box, Valenzuela’s ongoing project

His film Diamond Box, for example, is a study of undocumented migrant day laborers Valenzuela hired outside a Seattle Home Depot. He paid a dozen or so men an hourly rate to sit in a makeshift set built in the back of a box truck and tell their histories. The black and white video footage is gritty and beautiful, scintillating with silvery faces. The footage is divorced from the audio, chilling and dreamlike; you can’t tell which story belongs to whom. The interviewees sit, fidget, wait, as words disjointedly hover over images, subtitled onscreen. Stories of political and geographical transgression dissolve into a passage of portraits, radiant faces implying the moonlight of illicit night crossings. In one segment, a very young man with long lashes, head anxiously bent, looks sidelong off-screen while a Spanish-speaking voice describes life in exile and sleepless nights in unsafe places.

All of Valenzuela’s work is marked by minimalism and the tonality of dreams. In January, at the light-themed multimedia ONN/OF Festival in Ballard, Valenzuela simultaneously screened his two videos Emptiness and Light. He shot the footage a few months earlier at the Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works, two deserted saltpeter refineries in northern Chile that date back to 1880. Both films pulse with an uncanny rhythmic light, heartbeat-like. They navigate labyrinthine buildings frozen in time, moving through old schools, markets and tenement housing constructed of bone-dry slatted wood and plaster. Valenzuela’s camera floats like a disembodied eye through the space. He moves like a ghost.

***

Valenzuela was born in Santiago, Chile, in 1982. His father was a mailman; his mother sold tombs in cemeteries. The transition from Pinochet’s right-wing dictatorship to a fledgling socialist government played out during his childhood. But Valenzuela wasn’t preoccupied with politics or runaway inflation. His youth was rooted in the stories of Jorge Luis Borges and Manuel Puig, the poetry of Vicente Huidobro and the TV Westerns his grandfather watched every afternoon—distractions that would later inform his work. He also drew a lot, sketching characters from telenovelas.

He studied art history at the University of Chile, where he experimented with video for the first time, making short films based on stories by Borges, shot and edited quickly. During his last year at school, he received a large award from Sony for his short film L.E.A.H., which allowed him to fund increasingly complicated shoots.

The Builder #1, a 2011 black and white film/digital print, 50 x 40 inches.

By the time he was 22, Valenzuela had finished school and was teaching video editing at the University. But he was restless. He abruptly left Santiago and moved to Montreal. He could speak French (but not English), he had friends there, and most importantly it was close to the U.S.—his intended destination. For a year he slept on a stripper-friend’s couch, working odd construction jobs for little money.

One morning, Valenzuela woke up, counted 60 dollars in his pocket, and reckoned it was enough to get him across the border. So he walked there. Lacking proper documents, he was arrested, but he talked the police into letting him go. They put him on a Greyhound to Montreal, where he promptly turned around and headed back to the border. This time he crossed undetected.

Settling in Boston, Valenzuela worked illegally in construction. After a few years, he obtained legal status and traveled west to study philosophy and aesthetics at Evergreen State College in Olympia. Since then, Valenzuela graduated with an MFA from the University of Washington, where he’ll be teaching next year. He has shown work from Santiago to New York to Seattle. This past April, Diamond Box was one of 10 videos worldwide nominated for a Vimeo Award in the documentary category.

Diamond Box illustrates a type of voyeurism, Valenzuela’s studied observation of the small, often unconscious gestures that cumulatively fill hours, days, entire lives. He compares this preoccupation with detail to Baudelaire’s poem “To a Passerby.” The poem describes the swaying flounces of a woman’s skirt, the flash of her leg, a glance from her eye, then her sudden evaporation in a crowd: a romantic missed connection on a 19th century boulevard. Valenzuela searches for these fleeting gestures and concentrates on their political and poetic meaning. From them he constructs a universal language of movement, a visual method of storytelling.

“The soul of a poet, the mind of a scholar,” says Paul Berger, one of Valenzuela’s advisors at the University of Washington. “What else could you ask?”

***

Last year in Santiago, Valenzuela shot Marcha, two moving images shown side by side, like a diptych. The image on the right shows soldiers in crisp, white uniforms marching in tight formation with guns and drums, rehearsing for a military parade. They move as one, flawless and machinelike. The image on the left shows close-ups of dozens of off-duty soldiers passing time in a courtyard, sometimes shot so close a reflection of pavement is visible in the whites of their eyes. They stand around and fidget, unaware that Valenzuela’s telephoto lens is trained on them. When one soldier casually scratches his nose with the tip of his rifle, we see the institutionalized subject, the cog in the machine, become an individual again.

Artist C. Davida Ingram, who wrote an essay on Diamond Box for Valenzuela’s recent MFA thesis show, notes the “inordinate difficulty” in making political art that works aesthetically. “His images march in like a gorgeous Trojan Horse,” she says “By that time, you’ve fallen; he’s implicated you. In the best way. In doing so he gets you to look closely at the politics of displacement and migration that happen everyday around the invisible scar we call ‘the border.’ He shows you its human face.”

Valenzuela mixes up cinematic realism with experimental editing, cutting up scenes, rearranging reality to tell stories the way he sees and feels them. In conversation he references Godard and Truffaut—French New Wave auteurs who muddled the line between documentary filmmaking and storytelling. “The works exist in a strange transitional zone,” he says. “I’m concerned with forming a connection with the viewer all the time.”

Of course, Valenzuela’s tangled arrangement of oral history, video journalism, migrant memories and sense of place refer to his own history. Though he never goes so far as to explicitly describe his experience as an undocumented alien, the viewer infers autobiography pieced together from the subjects in his films. The artist hides behind the scrim of pseudo-documentary, but only barely.

“What I do is autobiographical,” Valenzuela says. “The films are one way of looking at yourself, finding a way to aestheticize that story. Ultimately it’s about engaging with other people, realizing that your story isn’t so unique as to have a connection with somebody else.”

Pictured above: Fixing the Architecture #1; a 2012 video still from Diamond Box, Valenzuela’s ongoing project; The Builder #1, a 2011 black and white film/digital print, 50 x 40 inches.