CITY ARTS, NOV 2015

Make it stand out

Revolutionary Voices

The latest multi-media performance by Degenerate Art Ensemble fights against silence.

by Amanda Manitach

City Arts Magazine, November 2015

Cover photo by Bruce Clayton Tom

Balancing atop the tower’s rim, Joshua Kohl and two assistants unspool hundreds of feet of red ribbon which the dancers catch and slowly reel in from below. Despite unforeseen winds and the palpitation-inducing 45-minute climb to the rim, the crew gets its shot of these five fictional spies, their carmine threads attached to imaginary drones that spread out into the cities to collect secrets.

Degenerate Art Ensemble dancers Sheri Brown, Alenka Loesch, Haruko “Crow” Nishimura, Jan Trumbauer and Paris Hurley during a video shoot at the Satsop Nuclear Power Plant in Western Washington. Photo by Bruce Clayton Tom

Dictator is DAE’s tenth evening-length work of Butoh-inspired multimedia, multi-art performance. It premieres at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco on Nov. 5 and debuts in Seattle on Dec. 3 at On the Boards. Weaving visual tropes of despotic overlords and rebellious fairy-tale princesses, Dictator tells the story of a repressed woman who finds herself physically and metaphorically without a voice. Appropriating tactics used by the regime, she lashes out, using her own forms of interrogation to give voice to the silenced masses.

Since it began 16 years ago, DAE has explored the psychology of fascism as a metaphor for the struggle of artists to surmount oppression. Dictator drives that message home with more opulence and complexity than ever before. This time, the performance will not only spill out into the audience, it will generate stories and an improvisational score in real time. It will be many things, but it won’t be easy.

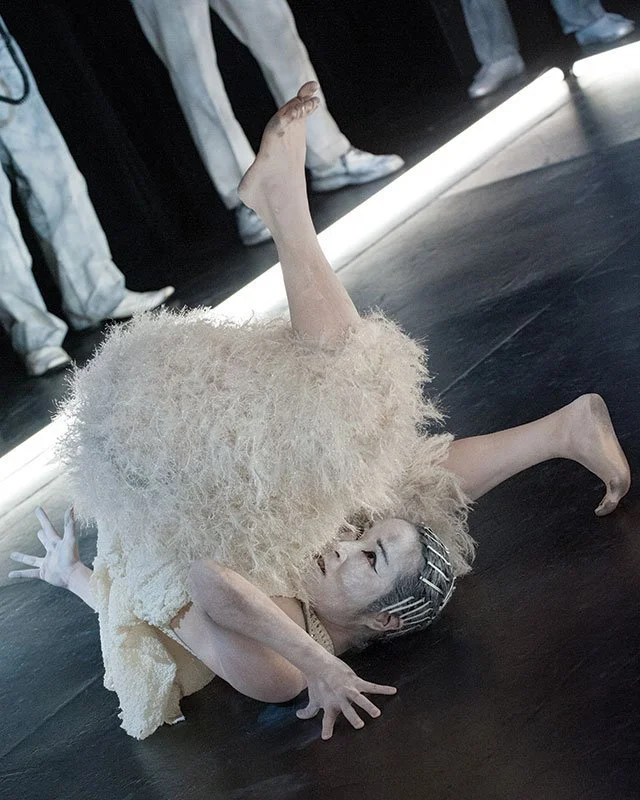

Haruko “Crow” Nishimura performing Underbelly in October 2012 in the subterranean spaces under and around the Space Needle.

Degenerate Art Ensemble was founded in Seattle in 1999 by co-artistic directors Kohl and Haruko “Crow” Nishimura. The company takes its name from the Degenerate Art Exhibition famously organized by the Nazi Party in Munich in 1937 to make an example of art that didn’t conform to conservative norms. Their performances combine butoh (a super-slow form of Japanese dance theatre that arose after World War II), ballet, anime, experimental music, fairy tales and the darker side of circus into furious, punk-rock happenings.

Nishimura and Kohl were born the same week in 1970. Their paths crossed for the first time when they were both 18 and studying at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston. Nishimura, who grew up in Japan, Syria, Australia and the U.S., thanks to her father’s job with the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, settled in Boston to study classical piano. Kohl had come from Mendocino, Cali., to study classical guitar. They were introduced by a mutual friend who was an opera singer.

For Kohl, it was love at first sight; Nishimura needed more convincing. They were married a year later, at the age of 19. Their first serious collaborations began after school, in 1994, with the Young Composers Collective, a 20-member orchestral performance group that performed in Seattle and San Francisco. From that seed Degenerate Art Ensemble grew, taking its current form in 1999.

From its inception, the group’s aesthetic was unlike anything else in the art world: Nishimura’s powdery skin and convulsive movements sheathed in elaborate, operatic gowns; the clattering, orchestral dissonance of Kohl’s classical-avant garde compositions, punctuated by the jangle of toy pianos. Their performances were obsessed with fascism, violence and the struggle for individual creativity. In the years since, Kohl and Nishimura have brought hundreds of collaborators and performers along for the ride.

“We move at a pace where we burn people out,” says Kohl. Four days before the Satsop shoot, he and Nishimura are seated upstairs at a Capitol Hill café, exchanging nervous laughter about the state of Predator Songstress: Dictator. Nishimura is wrapped in a thick sweater, a blue kerchief loosely tied around her hair. Mondo, the couple’s teacup Chihuahua, dozes in her lap.

With their 25th wedding anniversary on the horizon, the two still seem inseparable, even if their high-octane vision comes with occasional spats.

“Sometimes it’s hard to keep aspects of our lives separate,” Nishimura says. “I would like to be able to set apart time when we’re just lovers.” The scheming part of her mind just doesn’t turn off.

“She’ll be in bed at night still taking notes. I’ll be like, ‘I’m putting on headphones, I’m going to sleep, lalalalala’,” Kohl says laughing. “But we definitely both share the workaholic gene.”

Their incessant pace has birthed four European tours with DAE’s Big Band Garage Orchestra, three separate shows at On the Boards, multiple performances in San Francisco and tours of Germany, Slovenia, Los Angeles and Germany. In 2008 they debuted Sonic Tales, a concert-dance mashup featuring a cast of fairy tale characters like a Weeble Wobble princess who battled ninjas in a flaming-red gown and gyrated and spun and pirouetted onstage. The piece showed at the Moore Theatre in Seattle and traveled to the New Museum in New York the following year.

In 2011, DAE premiered Red Shoes at Frye Art Museum, a re-imagining of Hans Christian Andersen’s horror fairy tale about a girl who is cursed to dance herself to death. With Nishimura playing the doomed dancer, a public performance began in the museum’s galleries and flowed out into the streets of First Hill, winding through an abandoned grocery store, public fountains and a cathedral courtyard. Inside the museum, a retrospective included props from past shows and kinetic sculptures like an ice cream truck that served up surgical procedures and Nishimura’s Weeble princess gown from Sonic Tales.

A year later came a commission to reinterpret Phillip Glass’ Einstein on the Beach, which DAE performed at the Baryshnikov Center in New York. In 2014, DAE collaborated with classical chamber ensemble Kronos Quartet to celebrate the Neptune Theatre’s 40th anniversary.

In 2012, Nishimura was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship for choreography. Yet, with all the accolades and accomplishments DAE has logged, the co-directors remain mystified at their own creative process. Dictator is still in flux.

“I hadn’t had a panic attack in a decade,” Kohl says. “I had one a few weeks ago. But we had some breakthrough today at rehearsals.”

“We’re still trying to work out the ending,” says Nishimura.

Nishimura conceived Dictator as a total of six short pieces, portraits of anti-heroines amalgamated from historical and fictional women. One of the initial Songstress pieces was Degenerate’s Underbelly, performed at Seattle Center in 2012. An indigenous iteration of John of Arc was the first of the anti-heroines, followed by Gracie Hansen, the Seattle madam who created a topless revue called Sin Alley that showed at the 1962 World’s Fair and was shut down in the face of puritanical uproar. Performing as the central characters, Nishimura carved her way through the tunnels, loading docks and typically inaccessible rooms beneath the Space Needle. One scene was illuminated with gigantic, fluorescent light sculptures that moved around performers; another was filled with temporary subterranean wading pools.

By the time Kohl and Nishimura began on Dictator in spring of 2013, the piece had exploded beyond the vignette format. More than just another chapter in the anti-heroine saga, the story became an epic in its own right. In typical Degenerate form, the fairy tale world they constructed is unlike anything that’s come before.

“We didn’t want to go and make another 1984,” Kohl says. “The costumes are vibrant, colorful, a full 360-degrees from the grungy, black and white totalitarian cliché.”

During the 90-minute piece, Nishimura and Douglas Ridings will dance in front of a 9-foot by 30-foot projection screen illuminated with video footage from Satsop, Fort Warden, Fort Stevens and a tree farm in Oregon. The show features lavish costumes by Alenka Loesch, production design by Elizabeth Jameson, video by Ian Lucero and Leo Mayberry, massive 3-D rendering of landscape maps by Olson Kundig, light design by Ben Zamora and live music by Kohl, composer Benjamin Marx, violinist Paris Hurley and vocalist Okanomodé, in his first performance with DAE. In focusing on the human voice, it involves more singing than DAE has ever done.

“It’s amazing and a little scary,” says Okanomodé, who will be improvising throughout the performance. “I won’t have much time to pull it together. It really is about going inside, going within, connecting with the stories they’re telling, the stories they’re writing during the show.”

As Nishimura’s anti-heroine character Ximena—which means “listener” in Spanish—gathers stories, the regime lashes back. They invade her home, remove her to a penal colony and extract her voice. Rather than make a martyr of her, the state decides to make an example of her. They execute her brother, played by Ridings.

“Then something happens,” Nishimura says, “maybe metaphysical. The execution sets off a kind of Godzilla energy in her and her voice comes out in this ultra-power.”

Christian Swenson, Paul Budraitis and Mark Dalton on set inside a bunker at Fort Worden State Park for Predator Songstress: Dictator.

Nishimura’s onstage transformation mirrors a personal coming of age. Around the same time she began work on Dictator, she found an identity apart from her family history.

Nishimura’s family was born of an arranged marriage. “For my parents, making a family was an unconscious thing and the energy was very dark,” she says. “It’s been something I didn’t want to confront for a long time. Renaming is a part of that process.” She abandoned her given name and symbolically adopted the name Crow because the bird is of the Northwest.

“They are also survivors, troublemakers, mischief,” she says.

The evolution of Crow—person, muse, anti-heroine—gave birth to the Dictator’s narrative and precipitated an urgency to find not only her own voice, but voices for those who might not usually have access to a stage, or to tickets for the show.

“The story comes from a dark place, honestly,” Nishimura says. “As artists, I question why we so often perform just for the art audience versus a broader audience.”

Her interest in getting beyond the art audience evolved from Red Shoes. For an entire year following the premiere of that show at the Frye, Nishimura often took to the streets on her own, dancing in public spaces, without any music or costume.

“I had amazing encounters with people on the street, people I never realized would want to watch me perform,” she says. “It opened my practice up to more and more communities.”

During that time, Nishimura repeatedly found herself performing for members of Seattle’s homeless population. Afterward, she approached Path with Art, a nonprofit that offers arts opportunities to people recovering from homelessness and addiction. Eventually she developed a workable idea for collaboration and in the fall DAE hosted an intensive two-week-long series of workshops at Cornish College of the Arts, working with nine Path with Art students 10 hours a day to develop Dictator’s story. Okanomodé was among the performers rehearsing with the students during that time.

“DAE approaches working on their pieces as if it is ritual,” he says. “Ritual very heavily steeped in a sense of family. Everyone involved—we eat together, stick together, cry together. As artists we want to step lightly when bringing in people who have trauma, who might not have, in that moment, the same privilege we have. Joshua and Crow have spent a lot of time in the past year just listening, crying with them, connecting with them.”

Many of the students are artists themselves without regular access to mentorship or opportunity to develop. Nishimura and Kohl light up with smiles when describing how the students transformed after two weeks of workshops.

“This is a group of people who were already being probed by social workers, being interrogated,” Nishimura says. “We wanted to know how they would turn the tables, how they would interrogate society, to connect with humanity after so long being shunned, after a period when people wouldn’t even look them in the eyes.”

During the intermission in the middle of Dictator, a group of formerly homeless performers will take the stage as interrogators, posing their own questions to the audience. The stories that emerge will be worked into the second half of the piece, performed by Okanomodé and the other musicians. The intimacy and proximity of performers to audience is why they chose On the Boards as the venue for the piece’s Seattle premiere.

Lane Czaplinski, On the Boards’ artistic director, has watched DAE perform over the years, but Dictator is the first time he’s worked with the group on a full-length production.

“When I first got into this world, I thought all radical artists would be in their mid-20s,” Czaplinski says. “I found that most of the time it’s not the case: It’s artists 10 or 15 years after that, if they have their wits about them and still haven’t quit art. That’s where DAE is right now.”

While the uncharted territory is not without conceptual risk, DAE forges ahead, breathlessly.

“If we are talking about voice, we have to talk about not just the voices we’re used to hearing all the time, but beyond that,” Nishimura says. “Women, homeless, veterans, people of races other than our own. We want to find the voice of those hidden or shunned. It’s a very rich part of this ongoing collaboration. It’s an exploration that doesn’t seem to have an ending.”