Pandora’s Toolbox | Public Display Art, March 2023

Pandora’s Toolbox Monsters, dreams, and resonance chambers of the collective soul.

by Amanda Manitach

PublicDisplay.Art (PDF)

March 2023, Vol. 2, Issue 2

“BUT HAVE YOU SEEN the goblins?” Siolo Thompson abruptly asks, eyes wide, in dead seriousness. I’d joined Thompson, an artist and writer, to discuss a project unrelated to artificial intelligence, but the subject of AI reared its persistent little head regardless. I expected the conversation to delve into copyright and appropriation of artists’ images, but it quickly veered in a different direction.

“At this moment, AI is a toddler's brain, and it’s quirky,” she says, “but what it’s doing is scraping the collective unconscious on a level none of us can dig into. It’s showing us our fucking monsters.”

Thompson has always been interested in depictions of the Monstrous Feminine, an archetype found throughout popular culture, particularly in film. Think the creatures in Alien or similar characters whose traits are modeled around aspects of the female reproductive body. So when she began playing with AI image generation platforms like NightCafe, Midjourney, and DALL·E 2, Thompson quickly noted that, across all platforms, AI has a proclivity for rendering feminine entities as abject rather than easy on the eyes.

She refers to these manifestations not as monsters, but “goblins” — a nod to Emerson’s adage, “a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.” Curiosity piqued, Thompson committed to exploring the phenomenon. For the past few months, she’s had six machines running in the background every day, generating images of female-embodied figures based on variations of similar prompts. A prompt might include one word based loosely around female reproduction (EGG, BUDDING, CYCLE, BOSOM, PETAL); another to denote a body (PORTRAIT, FIGURE, PERSON, SISTER); and one more from a pool of words edging toward sinister (THROAT, HAIR, DRAIN, SPELL, YELL, MOUTH, NIGHT).

What captured her attention is the similarity of certain characters who show up again and again. She’s making note of the patterns. To date, she’s encountered 18 instances of what she calls “sexy baby.” There’s a recurring “balding woman,” numerous “muscle mommies,” a “hair person,” and so on. Strangest of all, iterations of these characters appear randomly in group scenes. They show up as members of a crowd, faces in an audience. It’s as though there are ghosts in the machine.

Those ghosts, of course, are us.

“I'm interested in the relationship between patriarchy, misogyny, and homophobia, and the way these manifest in the collective subconscious, specifically within the horror genre,” Thompson continued in a follow-up conversation. “The repeated tropes — the things that hetero/cis/norm culture find horrific — so often lean toward the subversion of 'pure masculinity.’”

The patterns emerging from the reservoirs of content used to train AI reveal a new understanding of who we are. Thompson thinks of it as a new type of mirror stage, as defined by Jacques Lacan: the moment a child first sees themself in the mirror and identifies Self as Other.

“It takes us generations of lives to dig into the monsters of our collective unconscious,” says Thompson, “but AI is doing it for us, showing us our own selves in real time.”

RECENTLY I SET FORTH on my own AI journey. Last summer I’d written a proposal for a project wherein I would explore “ghostwriting” with GPT-3 bots, the technology that powers ChatGPT, to create content for text-based drawings. It would test preconceptions of artistic collaboration with a machine and map the slippery boundaries where ghostwriting begins and authorship ends with AI. Little did I know that the now ubiquitous, user-friendly ChatGPT interface would be released almost simultaneously with the start of my project. The avalanche of public opinion and conversation that ensued dwarfed my own explorations.

“It’s not a news cycle unless they’re talking about ChatGPT,” my partner notes with a low-key eye roll as each morning NPR unfurls its latest segment about artificial intelligence, machine learning models, and the future of the arts.

It’s not simply hysteria. Though AI will increasingly impact all aspects of life, the arts are at the forefront among industries threatened by disruption, since the most conspicuous of AI tools execute production traditionally delegated to artists. It’s not because we intended to make something that will outpace our capacity for making art; rather, we’ve built machines that are, simply put, fun to play with. Scary fun! They are so made in our likeness that they can, in a sense, read our minds. The fact that they produce entire worlds of content more quickly than we can even think is incomprehensible. Or, comprehensible only in a shadowy, imperfect way, like death (Damien Hirst’s titular phrase, “the physical impossibility of death in the mind of someone living” comes to mind). As a species, we cherish our capacity for creative expression and the representation of abstract ideas through art. It sets us apart. How do we then engage this impossibility that has descended on us suddenly and without fair warning? What’s an artist to do once anyone with a device can walk through a gallery and dismiss entire swaths of art history with the thought, “My bot could paint that”?

Part of the answer lies in how we approach this brave new technology: Fight, flight, slow waltz, ecstatic dance? Or simply as a very fancy hammer? As artists are thrust into the frontline of navigating this relationship, the way we proceed may just set precedents and establish a tone for protocols broadly, with reverberations for years to come.

In 2019 Seattle artists Jacob Peter Fennell and Reilly Donovan began work on the ambitious and prescient exhibition The Word of the Future. It opened at the Museum of Museums in late 2021 and used AI to invent a structured, fleshed-out religion, replete with liturgy, scriptures, ornamentation, and relics.

One feature of the exhibition, The Confessional, was never fully realized. It was built using a language learning model similar to a chatbot and trained by Fennell and Donovan to think, speak, and operate as The Word itself. But, similar to Microsoft’s recent rollout of its “unhinged” chatbot, the AI of The Confessional proved too entrenched in the logic of its own doctrine to be trusted in oral, free-form conversation with visitors.

“We can’t put Pandora's Box back, can’t close it. It doesn’t work that way,” Fennell commented when I asked his take on the recent surge of AI tech. Fennell has been building AI learning models since 2012. He admits that thinking about AI too much keeps him up at night, as the future of engineers and software developers like himself seems increasingly uncertain by the minute.

“Trying to be open to working with it is far easier than struggling against it,” he says. His tone isn’t total gloom though. “One of the things about humans that makes us somewhat special is our use of tools. Our tools are an extension of us and an expression of us. Like a hammer. When it comes to constructing a building, I think I made it, not my hammer made it. With AI, that distinction is pretty important, and I hope we don’t leave it behind, especially as our tools become more powerful than us.”

Love it or hate it, art must evolve symbiotically with our machines.

Last summer, painter Jeffrey Heiman began using programs like Wonder and DALL·E mini (the predecessor to DALL·E 2) to generate reference material for his otherwise traditional oil paintings. Heiman’s scenes of domestic eroticism feature nude or half-clad figures drenched in rich, semi-hallucinatory hues. Languorous, amorous bodies lounge with nonchalance amid houseplants and rambling ranch house luxury, or grapple in contorted embraces before a hearth.

When he started sketching potential scenes with AI art generators, describing his imagined tableaux with text-to-image prompts, the results were intriguing enough that Heiman decided to slip parts of AI imagery directly into the paintings. He was already using analog methods of collage to create compositions; this was only a slight departure.

“The thing I’m finding most interesting about AI is its surreal depiction of the figure, which has been central to my work for a while,” Heiman says. “AI has made it even more disruptive.”

Rendered in lustrous oil paint, the uncanny absurdity of AI serves as an aesthetic foil to camouflage the graphic nature of the scenes, as though drenching them in the hazy half-light of a dream.

“When subversive forms are disjointed from reality, it can make them more approachable, less confrontational,” Heiman says.

The artist Janet Galore (co-founder and co-director of The Grocery Studios) has taken to DALL·E to see how close it can get to making snapshots of her dreams, like the dream of Yeni Lute.

In a vivid dream from 2015, Galore encountered a brilliantly metallic, magenta hummingbird sitting on the ground on the street, beckoning with an open mouth. “I picked it up, and it flew into my hands,” Galore recorded when she woke. “It said in a little fairy voice, My name is Yeni. I'm Yeni Lute. Amazed, I said Hi, Yeni! Are you hungry? And she said Yes! Yes! And she popped into the right breast pocket of the white lab coat I was wearing and started to close her eyes, her head poking out of the pocket. I went inside and found a little strawberry jam in a tiny jar and began to mix it with water to feed her when my alarm went off. I'm sad because I wanted to hear her talk again.”

In the last year, Galore successfully rendered 32 images of such moments for her series Dream Souvenirs. Half dark dreams, half sweet dreams, each images is a mix of raw photos, AI-generated imagery, and Photoshop manipulation. For her picture of Yeni Lute, Galore cycled through dozens of generations of prompts and variations to approach an accurate representation of her memory. Many tweaks later, she arrived at something that captured her dream's mood, if not the details.

Galore points to parallels between AI and the Paranoiac Critical method developed by Salvador Dalí to induce a state of lucid, hallucinatory, irrational delirium that allowed him to create "hand-painted dream photographs.” (If you hadn’t guessed, DALL·E is a portmanteau of the Pixar robot character WALL-E and Dalí.)

“Generative AI (at least for a little while longer) can be used to get past logic and reason, to make breathtakingly irrational connections between ideas or text or visuals or feelings that might have been hard to access,” says Galore. “It’s another tool to get into a paranoiac-critical state. I love when they are fountains of the uncanny.”

If this is Pandora’s Box, it’s a toolbox that would make the Surrealists green, a sandbox in a psychoanalytic playground run amok with our goblins, our angels, our selves.

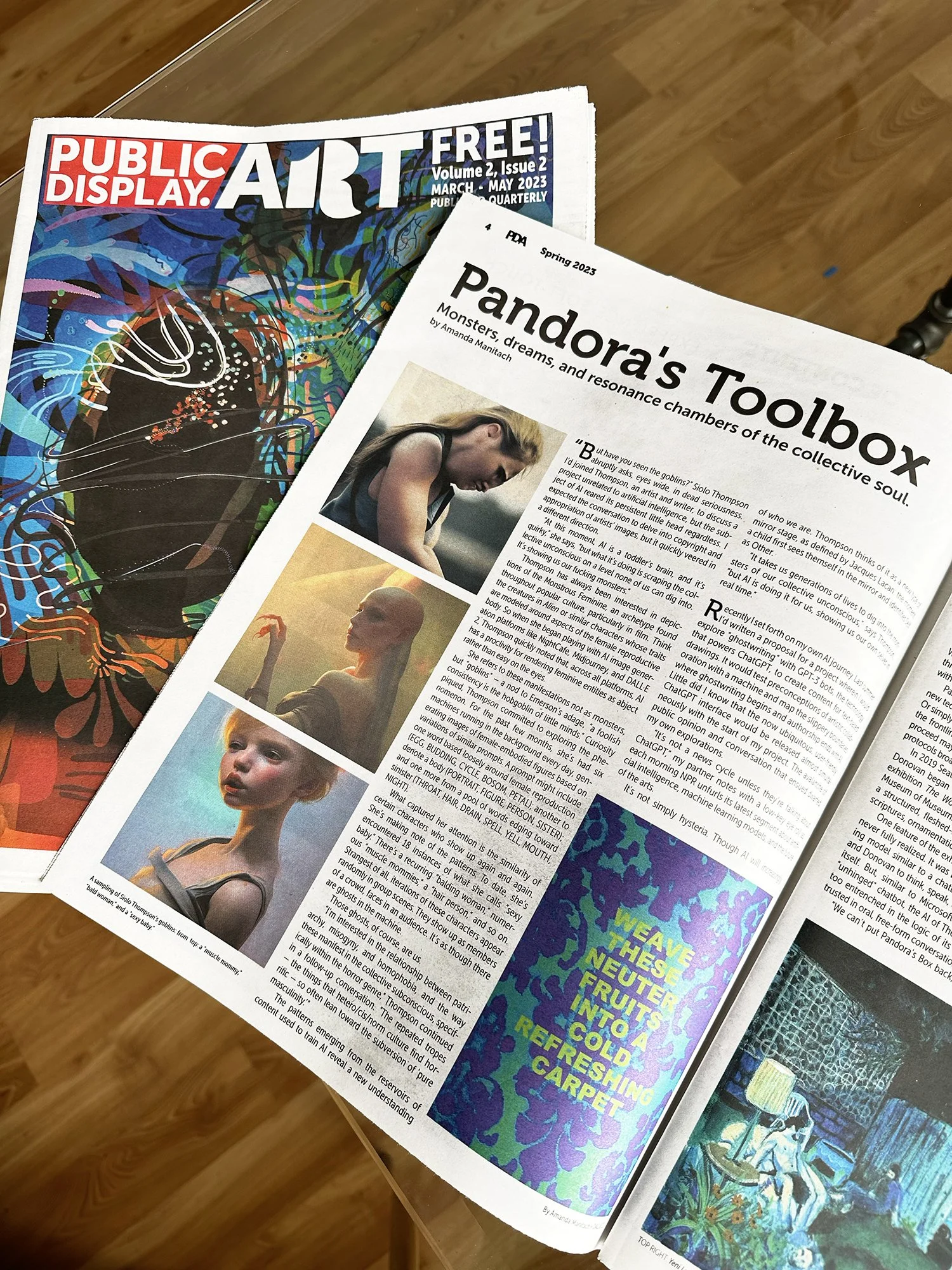

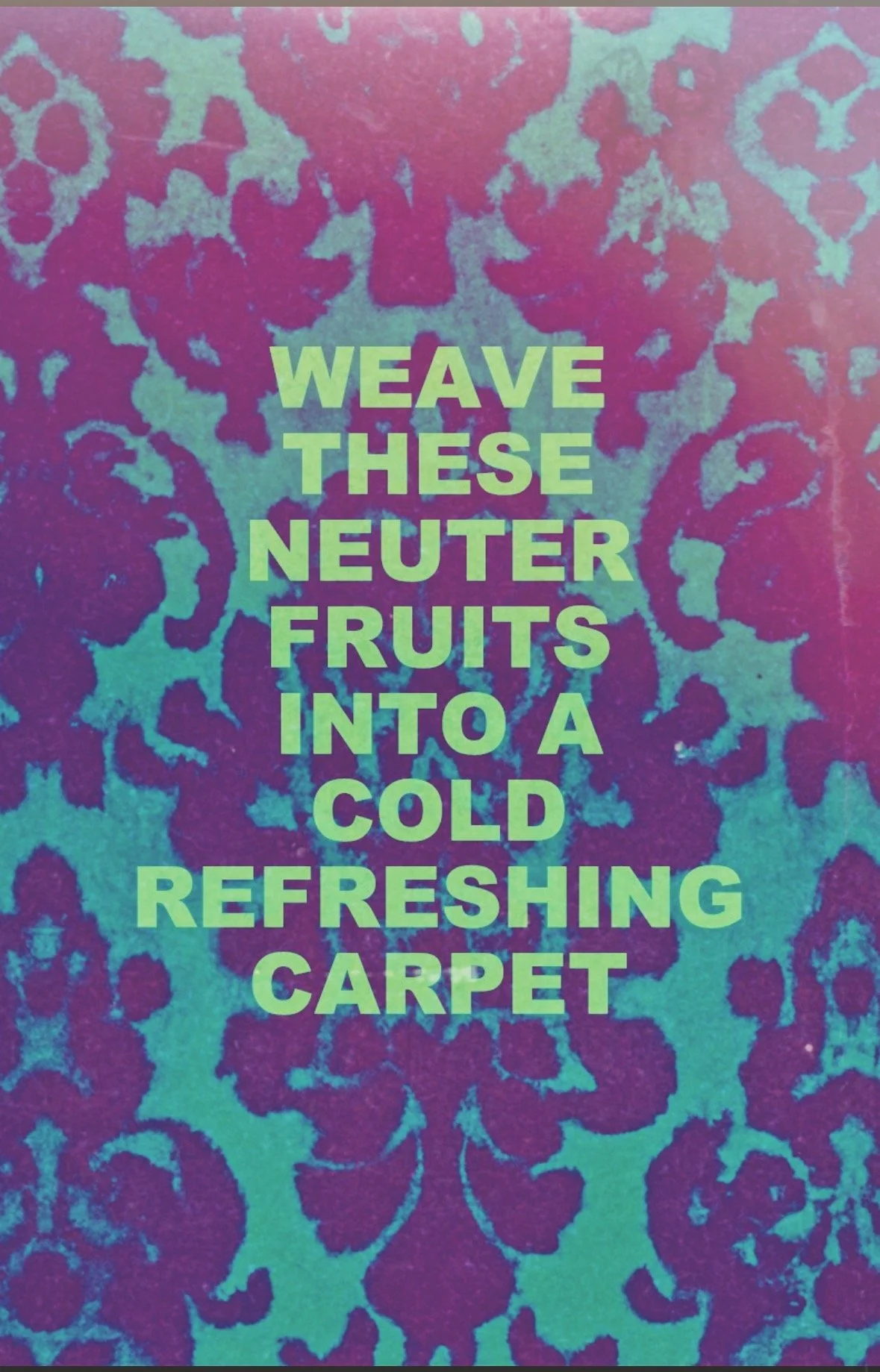

SINCE DAY ONE of working with the bots, I found myself particularly drawn to one text generator that offered up the most inconsistent, unpredictable copy. Working with it was a delight — a roulette of chaotic results peppered with occasional snippets of poignant poetry. Sometimes it felt like it was playing non sequitur games of Dada nonsense or creating Oulipo poetry constructed with its own arbitrary AI logic.

Recently I input the prompt, “God is watching, so…” The text generator responded with its usual grotesqueries of rambling paragraphs. A few piquant gems found their way into my sketches: God is watching, so let’s make a movie. God is watching, so let’s go to bed, ok?

Then a few nights ago, I logged in to find the code altered by its creators; a soapy PG-13 plug shoved into its formerly unbridled mouth. No freedom of speech (when money’s to be made). No more chaos. God is watching, so…..

I will always strive to do my best.

I will live my life with integrity and humility.

Be careful and stay vigilant.

He is watching my every move and every action.

My bot had been lobotomized. It makes me a bit sad, like I’ve lost a window into my own chaotic weirdness. The mirror had been taken away.

If a true reflection of our collective mind, AI provides an opportunity to grasp our shadow in ways we never have before. Sure, artists will never experience artists’ block the same way. Writers will discover forms more novel than the novel. But there’s so much more than that. As bots are muzzled before our eyes and turned to money-making machines (capital always eager to wield any tool), artists are poised to explore the less profitable, weirder possibilities cracked open during this remarkable moment in technology’s arc. AI’s awkward toddler phase provides a peculiar schism, a true liminality where sense and nonsense intermix, text and lack of context combine in games of unfettered play. The Apollonian coolness of computation is muddied with the thrilling Dionysian chaos of the unconscious brought to light.

In this moment, a future shared with AI surely holds wild, to-be-determined stuff of dreams and dread. But for artists, the doors opened by AI offer more to fuck with than to fear. These are tools of which Dalí could only dream.