Fentanyl, So Far | Public Display Art, May 2023

Fentanyl, So Far

Shiny husks of death

By Amanda Manitach

Public Display Art

May 2023, Vol. 2, Issue 2

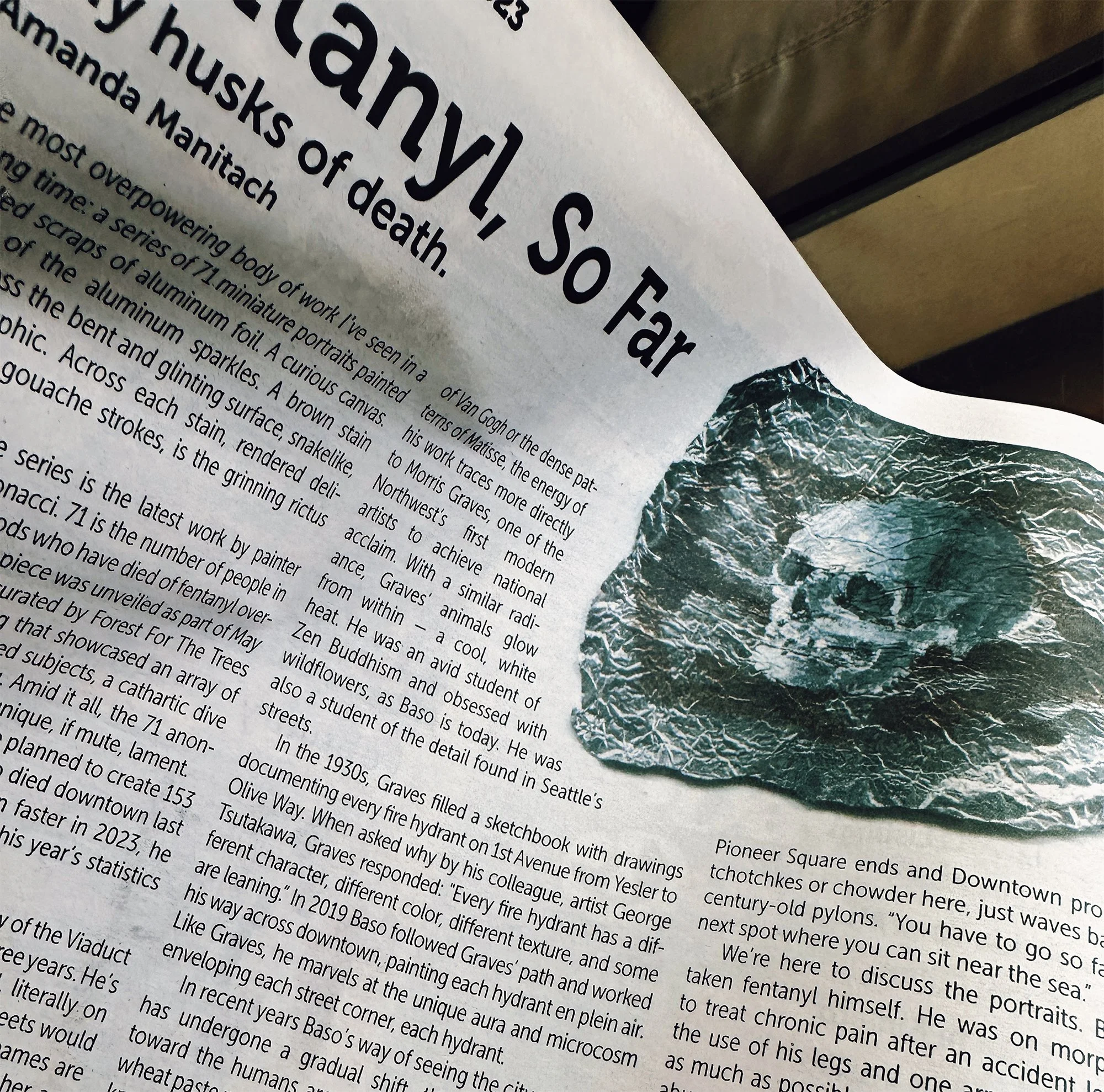

IT’S THE MOST OVERPOWERING body of work I’ve seen in a very long time: a series of 71 miniature portraits painted onto crinkled scraps of aluminum foil. A curious canvas. The wrinkle of the aluminum sparkles. A brown stain meanders across the bent and glinting surface, snakelike, almost hieroglyphic. Across each stain, rendered delicately in opaque gouache strokes, is the grinning rictus of a sightless skull.

Titled So Far, the series is the latest work by painter and muralist Baso Fibonacci. 71 is the number of people in downtown neighborhoods who have died of fentanyl overdoses so far this year. The piece was unveiled as part of May Showers, a group exhibit curated by Forest For The Trees and ARTXIV earlier this spring that showcased an array of luscious, dark-toned or -themed subjects, a cathartic dive into the storm before the spring. Amid it all, the 71 anonymous faces of So Far unfurled a unique, if mute, lament.

When Baso began the series, he planned to create 153 pieces — the number of people who died downtown last year. But as the numbers spiked even faster in 2023, he decided the series should document this year’s statistics in real time.

BASO LIVED ON ALASKAN WAY in the shadow of the Viaduct for a decade, and in SODO for the past three years. He’s experienced the fentanyl epidemic firsthand, literally on his doorstep. Though his knowledge of the streets would make a flaneur blush, Baso Fibonacci (whose names are borrowed from the Tang dynastic Zen philosopher and the Italian mathematician, respectively) grew up on Tiger Mountain in the Cascade foothills surrounded by bears, foxes, and deer. Accordingly, the art he’s come to produce occupies a space where the extremes of the natural world and urban landscapes overlap, meld, and collide. Over the years, his murals have graced many familiar corners of the city: a triptych of floral bouquets across the facade of Fred Wildlife Refuge (RIP), or his sweeping mural that runs along the SODO Track depicting a wolf catapulting through a cityscape caught on fire.

Whether painting flower arrangements or forest wildlife, Baso has never leaned into hyperrealism. Instead, his subjects radiate aggressive, vibrant brushstrokes rendered in surreal jewel-tone color. Feverish marks pulsate. While the style harkens to the thick, impasto brushstrokes of Van Gogh or the dense patterns of Matisse, the energy of his work traces more directly to Morris Graves, one of the Northwest’s first modern artists to achieve national acclaim. With a similar radiance, Graves’ animals glow from within — a cool, white heat. He was an avid student of Zen Buddhism and obsessed with wildflowers, as Baso is today. He was also a student of the detail found in Seattle’s streets.

In the 1930s, Graves filled a sketchbook with drawings documenting every fire hydrant on 1st Avenue from Yesler to Olive Way. When asked why by his colleague, artist George Tsutakawa, Graves responded: "Every fire hydrant has a different character, different color, different texture, and some are leaning.” In 2019 Baso followed Graves’ path and worked his way across downtown, painting each hydrant en plein air. Like Graves, he marvels at the unique aura and microcosm enveloping each street corner, each hydrant.

In recent years Baso’s way of seeing the city and world has undergone a gradual shift, the focus tilted more toward the humans around him. Consider his series of wheat paste portraits of the homeless people he’s come to know in Pioneer Square over the years: Twelve full-length figures, rendered in vibrant color, larger-than-life, were pasted on the pillars of the Viaduct before its demolition and lit from below. He hosted an outdoor feast for the show’s reception, where any and all were welcomed to celebrate the community. In 2021 he completed a series of portraits of 20 Washingtonians who died from COVID-19 that year. The paintings were displayed in South Lake Union as part of Shunpike’s Storefronts Program. With each series, Baso’s intent becomes more pronounced: to quantify something that seems intangible, to render the invisible not just visible, but personal.

“THIS IS THE CLOSEST SPOT where you can chill by the water,” Baso says as sunlight gently beats down on an unseasonably summery day in May. He’s brought us to one of the old sun-bleached commercial docks where Pioneer Square ends and Downtown proper begins. No tchotchkes or chowder here, just waves battering against century-old pylons. “You have to go so far to get to the next spot where you can sit near the sea.”

We’re here to discuss the portraits. Baso has never taken fentanyl himself. He was on morphine for years to treat chronic pain after an accident left him without the use of his legs and one arm, but he avoids opioids as much as possible. His older brother died from heroin abuse, he explains. Baso was only 15 at the time.

“I’ve always been really careful because of it,” he says. “When I was growing up my mom would come into town to find him on the streets in Seattle. He was always somewhat of a mystery in my life, because he got hooked on drugs so young and I would only see him once in a while.” The exact cause of his brother’s fatal overdose is shrouded in mystery, as he had become entangled in running drugs across the Mexican border. The precise circumstances of his death were less important than the impression it left: “I was always very aware of what that could do to someone,” Baso says.

He’s known people who smoked fentanyl well before it was available on the streets, before it was a household name. Friends have smoked it. Friends have died from it.

“I don’t think the public understands fentanyl at all,” he continues. “People hear about it and are like, why don’t they stop? They don’t understand the severity of the withdrawals. If you stop, you’re sick for at least a week. You can’t sleep, can’t get comfortable. Then there are the underlying factors of why people use fentanyl. Either people have physical pain or they have emotional pain. Opioids help with both. They don’t help solve it, but they erase those things for the temporary moment.”

The decrease in the global supply and trafficking of heroin over the past decade would have been grounds for celebration had Americans not acquired a taste for pills. In 2019 headlines prognosticated what the rise of the super-opioid fentanyl might look like in five years. Fewer than five years have passed, and things are worse than anyone guessed. The unfettered production of fentanyl, coupled with the economic fallout from the pandemic and the resulting surge of homelessness, has proven devastating.

It’s a difficult truth that for those who can’t access prescription medication — let alone shelter — the meth-fentanyl cocktail is the closest thing to a socially acceptable prescription cocktail of antidepressants, Adderall, and Xanax. In fact, Adderall and Xanax, along with oxycodone, is the medication most commonly mimicked by black-market distributors of counterfeit pills containing fentanyl and methamphetamine.

Because fentanyl is 50 times stronger than heroin and its effects only last a few hours, there’s no preventing brutal cycles of euphoric come up and excruciating comedown. According to recent reports, M30s (counterfeit oxycodone pills, or “blues”) on the streets in Seattle can be bought for around a few dollars apiece. Regular users might smoke one or more pills an hour throughout the day. Blues make heroin look manageable.

The shift in Seattle from a long and tortured history with heroin to a nascent more deadly affair with fentanyl is something to which Baso is acutely attuned.

“I’ve been noticing how you work on projects that sometimes you don’t finish, then the city changes, and then the work isn’t relevant anymore,” he says. “In Seattle, I don’t think we’ll have this fentanyl culture in ten years, maybe in five years, which is a good thing. But it’s one of the points of this piece, too: one day, it’ll be gone. This is a way to talk about it, to remember it, and in the future, people will understand it better.”

A work of art this aspirational risks waxing sensational or didactic, or spiraling into realms of politically weaponized rhetoric. So Far deftly walks a fine line and avoids any of that. Each square of foil used in the series is personally sourced from users, or found on the streets. The burnt umber stain that wends and creeps along the foil is a mark left by a burning pill. The process of procuring these items is personal and painstaking, anything but glib.

One friend, a former user, offered up a large number of foils she’d saved. Most of the rest were found. “When I started collecting the foils, a lot of it was just roaming and scouring all the main alleys downtown, picking them up off the ground. I might find five, but only two that weren’t falling apart too much to work for a painting.”

Users are quick to offer Baso fresh foils, assuming anyone asking must want to smoke.

“When I tell them what I’m collecting it for, we end up talking about the drug,” he says. “They all — without fail — are hyped on what I’m doing, because all of them have had friends who died from it.”

Baso speculates that this year will witness the peak of Seattle’s fentanyl crisis. Public Health – Seattle & King County publishes annual end-of-year fatal overdose statistics by neighborhood. But midyear, only the countywide numbers are regularly updated. To approximate real-time numbers for downtown, Baso did the math based on King County and Downtown figures from 2022 and applied the ratio to the current county statistics.

“When you look at the data, it looks like we’ve crested the top of that curve. It looks as though the numbers may be going down,” he says. “But it’s going to be around for years.”

As much as So Far is a product of crunching numbers on King County reports, the point of the work is to unravel the abstraction of those data sets. People are bad at empathizing with an epidemic understood as numbers.

It occurs to me where I’ve seen these paintings before: They’re descendants of Van Gogh’s skeleton flagrantly smoking a cigarette. They’re echoes of James Ensor and his throngs of ghoulish revelers, the grinning jaws and bones of which seem to rattle under their Victorian frippery. There’s something less carnivalesque about this host of anonymous faces suspended between plates of glass, checkering the vast flat white gallery wall — yet there’s no mistaking the sense that maybe this is the 19th century calling, whispering reiterations of the thing that Baso intuits: cities change, situations shift. The wheel keeps turning but the lessons remain the same. We won’t learn if we don’t remember. As Baso continues to expand and evolve what it means to paint a portrait of the city, it’s evident that the faceless faces are more than memento mori. The fragile, singed paintings — easily cradled in the palm of one’s hand — are calling cards from beyond time, beyond death. They are reminders that compassion is a matter of survival.